Why math should be formalized - and resources to get started

Proof assistants enable us to formalize mathematics: to express arbitrary mathematical statements and proofs without ambiguity, and to automatically verify their correctness. Here I give some arguments for why math formalization might soon become inevitable. I also include some resources on formalization for the interested reader.

In a future post I cover how Artificial Intelligence will help us in scaling up math formalization (but here I do cover how it will probably force us to).

Contents

TL;DR

I believe that most of the new, main mathematical claims in the nearby future will have to be formalized. I make three main arguments, which, in my opinion, go in increasing level of strength:

- There already exists a lot of math (perhaps too much).

- Humans make mistakes.

- There will soon be an explosion of AI-generated math.

Too much human-made math

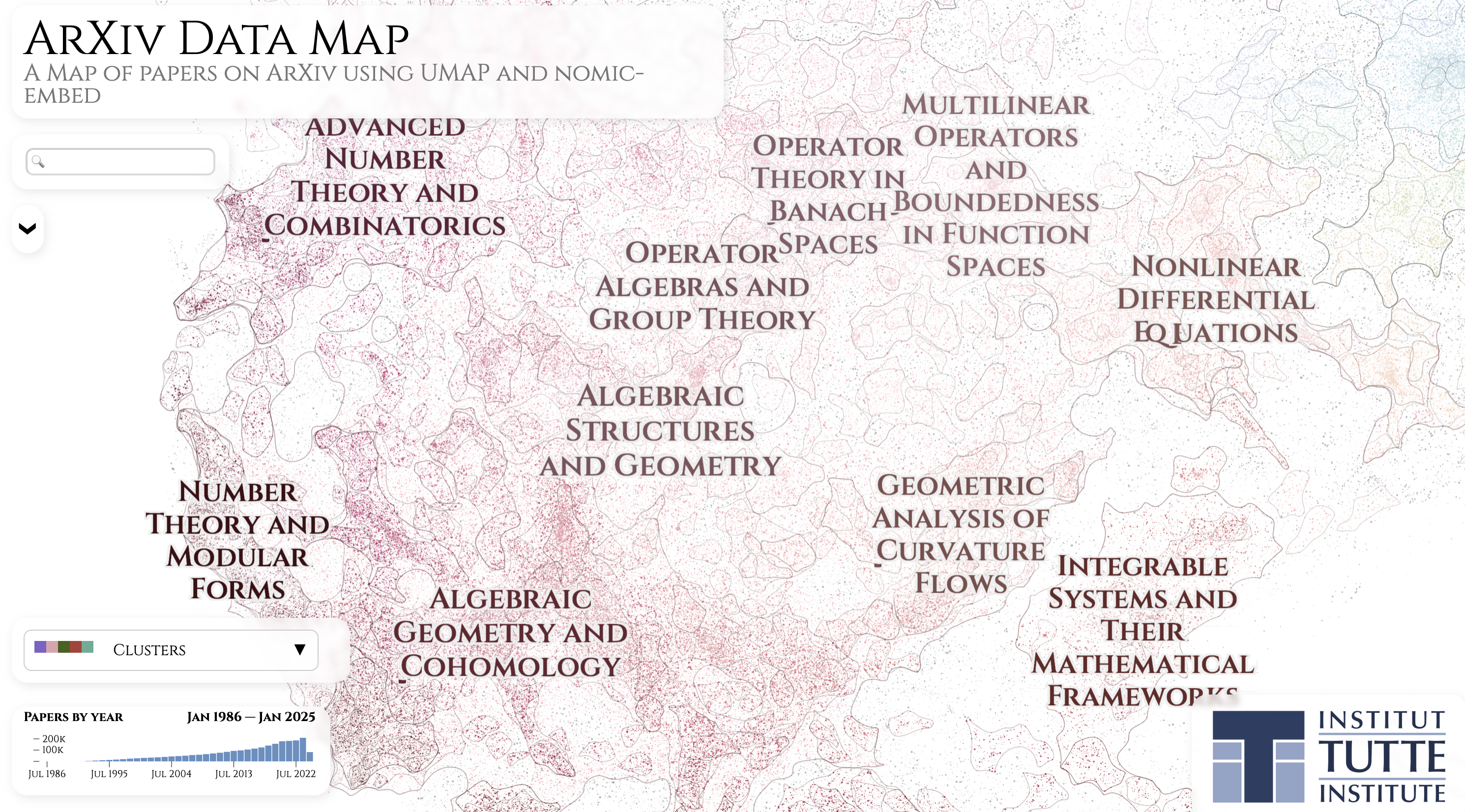

A portion of the awesome arXiv Data Map interactive visualization.

The first claim is simple: there already exists a lot of math. There already are instances (and there will be many more) in which a single person cannot verify the validity of a statement, since it depends on more results than what they can possibly verify. The typical example is the classification of finite simple groups, which, although believed to be correct, spans over 10,000 pages, scattered across hundreds of papers by many authors, and uses many deep sub-theories, which no single human masters. Moreover, some parts are only really understood by a few experts, which is a somewhat fragile situation. For more about the story of classification of finite simple groups, and how things piece together, you can check [Aschbacher. Notices AMS] and [Solomon. Bulletin AMS]. But at the end of the day, each piece has been peer-reviewed by experts, and gaps that have been found have been corrected.

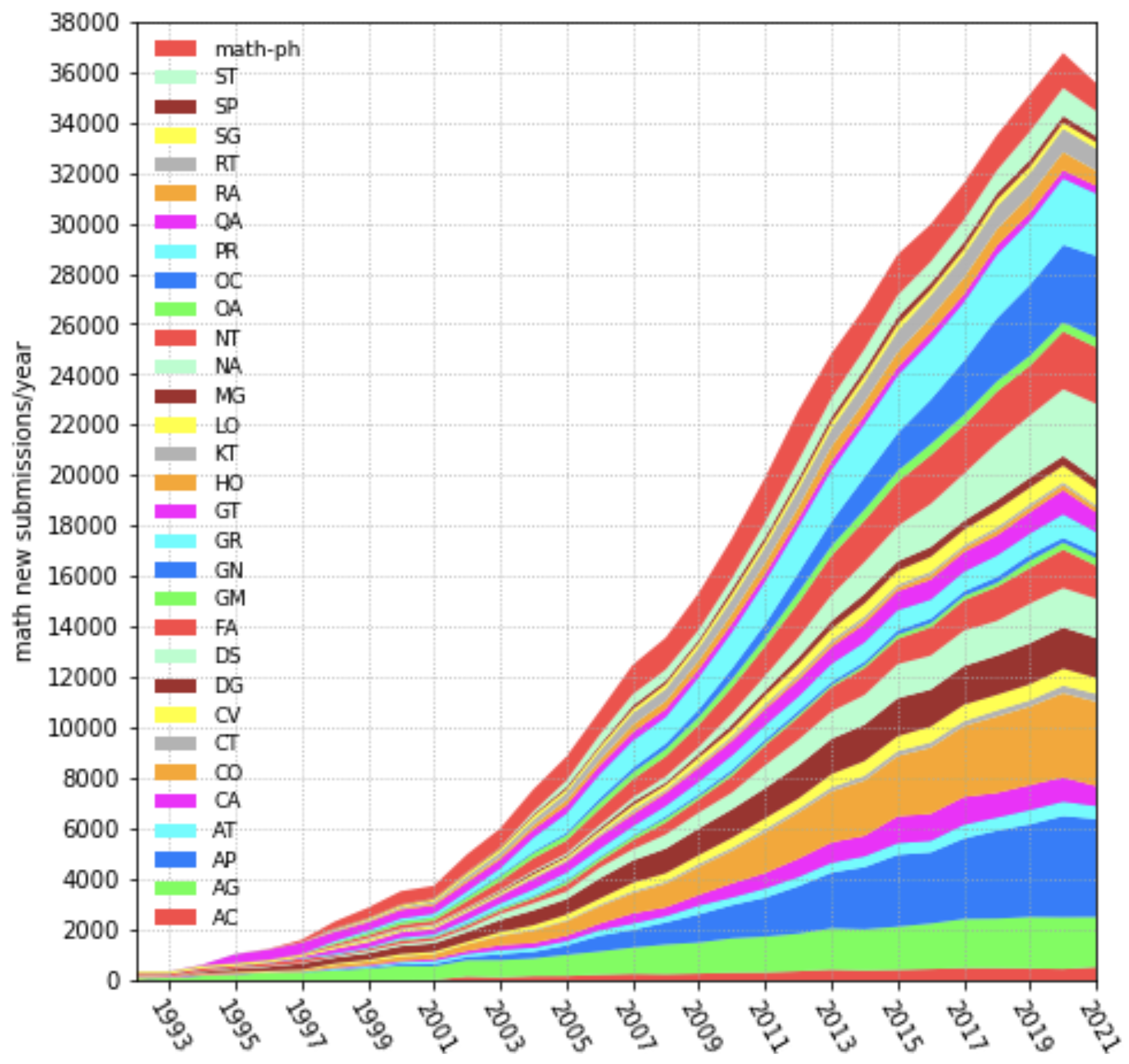

Number of math papers posted on arXiv per year (1993-2021). Image from arXiv submission rate statistics.

Gaps… This takes us to the second point. When doing informal mathematics, humans can make mistakes that are very hard to spot. Indeed, there are many past and current instances of important mathematical claims whose validity was or is contested by experts. I will mention some well-known instances, but I want to emphasize that the point here is not about who’s wrong or right, but rather about the fact that, even though mathematics deals with absolute truths1, in practice experts can disagree about the validity of important mathematical claims.

The abc conjecture. This is a conjecture in number theory from the 1980’s and the name comes from the fact that it involves three positive, relatively prime integers $a$, $b$, and $c$ satisfying $a+b = c$. The mathematical statement is not super technical, but it does not matter for this discussion. A positive answer to the conjecture implies a positive answer to several other conjectures in mathematics[Waldschmidt], making the problem important. Since it was originally stated, there have been several claimed proofs of the conjecture that have not been accepted by the mainstream math community. The most well-known instance is the one in the $\sim 600$ page series of papers [Mochizuki. PRIMS], whose validity has been the object of much debate, in particular by experts in the area who have published explanations for why they believe that the proof is incorrect[Scholze, Stix][Scholze].

An example from Machine Learning. The Adam optimizer[Kingma, Ba. ICLR] is a staple of modern Machine Learning, being the go-to optimizer for lots of standard architectures. In the paper that introduces it, it was shown that the method converges when optimizing a convex function. It was shown a few years later[Reddi et al. ICLR] that the original proof had a gap, and that convex functions exist for which Adam does not converge (although that did not stop anyone from using Adam).

A version of the homotopy hypothesis. This one’s a bit more abstract. It concerns a result, claimed in [Kapranov, Voevodsky. Cah. Topol. Géom. Différ. Catég.], published in 1991, which (very) roughly says that every space can be constructed using a special kind of recipe. In 1998, [Simpson] was made public, which contained a counterexample to the above claim. Voevodsky, one of authors of the first article (and a Fields medalist), writes in [Voevodsky. Institute Letter]:

Kapranov and I had considered a similar critique ourselves and had convinced each other that it did not apply. I was sure that we were right until the fall of 2013 (!!).

The letter is about how Voevodsky became interested in the foundations of mathematics and proof assistants, and I can’t recommend Voevodsky’s letter enough. It contains other interesting stories about incorrect claims such as the following (which concerns a different mistake):

This story got me scared. Starting from 1993, multiple groups of mathematicians studied my paper at seminars and used it in their work and none of them noticed the mistake. And it clearly was not an accident. A technical argument by a trusted author, which is hard to check and looks similar to arguments known to be correct, is hardly ever checked in detail.

Voevodsky went on to develop Univalent Foundations, an approach to the foundations of mathematics based on Type Theory and Homotopy Theory, which I hope to cover in another post.

Other examples. There exist more examples of incorrect or contradictory claims in the literature; Kevin Buzzard’s article Formalising mathematics: an introduction mentions an instance of two published papers that contain contradicting results, with both papers being published in the Annals of Mathematics, possibly the most well-reputed mathematical journal! The following related Math Overflow threads contain some examples as well:

- Widely accepted mathematical results that were later shown to be wrong?

- Results that are widely accepted but no proof has appeared

- Why doesn’t mathematics collapse even though humans quite often make mistakes in their proofs?

The top answer in the last thread, by Shulman, makes a good point:

I think another reason that mathematics doesn’t collapse is that the fundamental content of mathematics is ideas and understanding, not only proofs. […] usually when a human mathematician proves a theorem, they do it by achieving some new understanding or idea, and usually that idea is “correct” even if the first proof given involving it is not.

Tao makes similar points in the blogpost There’s more to mathematics than rigour and proofs. However, the part that I left out from Shulman’s comment reads as follows:

If mathematics were done by computers that mindlessly searched for theorems and proof but sometimes made mistakes in their proofs, then I expect that it would collapse.

And this takes me to the third point.

Too much AI-generated math

Because of generative Artificial Intelligence, it will soon be possible to produce a huge amount of plausibly-looking mathematical claims and proofs; far more than what humans can verify. Will the arXiv get flooded with AI-generated math-looking content? Will math journals be flooded with AI-generated submissions? I think that this is entirely possible, which is a problem due to the human-AI asymmetry of informal math:

Both a human and an AI can produce informal math, but only a human expert can verify it.

And I do not expect this to change easily.

If one cannot verify the math itself, one could try to filter submissions by, say, the authors’ or institutions’ trustworthiness, or by using AI as a preliminary judge, but these approaches would likely be deeply unfair and so imperfect as to not really address the problem. Ethical questions of this kind are considered in Emily Riehl’s talk Testing Artificial Mathematical Intelligence2, which I highly recommend.

It is not clear if there are good solutions. What is clear is that formal mathematics does not have this problem, since it can be checked automatically by a deterministic program.

Will formalization be enough?

Suppose that we do get the mainstream mathematical community to back up any important claims with a formalized proof. Will this overcome the issues presented so far? It seems to me that the points concerning errors or gaps (human or AI) will be addressed, but I see at least two remaining hard problems.

One is that a human expert would still have to be involved in interpreting the results that have been formally proven. A formal proof could look as if it is proving a breakthrough result, but after unfolding the definitions it may become apparent that what is proven is actually something much weaker. Relatedly, the talk by Emily Riehl that I referenced above proposes the following bar by which to judge AI-generated mathematics, which highlights the fact that human experts are still needed even for formalized results:

Any artificially generated mathematical text will not be considered as a proof unless:

- It has been communicated in both a natural language text paired with a computer formalization of all definitions, theorems, and proofs.

- The formalization has been accepted by the proof assistant and human expert referees have vetted both the formalization and the paired text.

The second problem is that we could still end up in a situation in which we are flooded by correct, formalized claims, and where it is not clear how to sort through all of these claims. In this case, there will have to be a radical reorganization of how the mathematical community produces and publishes math. This quickly leads us to the broader question of how the advancement of AI will force us to reconsider how lots of aspects of society work, an important example being education. There’s a lot of work to be done here, and it is outside the scope of this post. I just want to acknowledge the fact that the solutions we arrive at concerning a flood of AI-generated content will most likely go well beyond math.

Resources to get started

Here are some resources in case you are interested in math formalization. I’ll try to keep this concise, and I will not mention AI-related options for now: there are enough basics to learn as it is.

The first step is to choose a proof assistant, and there are many choices here. In fact, the real first step is to choose a foundation for mathematics! Many of the modern proof assistants are based on Dependent Type Theory (more specifically, the Calculus of Inductive Constructions), but not all of them.

At the moment, the de facto default choice of proof assistant to do math formalization is Lean 4, which is based on Dependent Type Theory; but if you want to learn about other choices, a good starting point is the series of talks Every proof assistant and a recent talk by Jon Sterling on developing modern proof assistants. I say “de facto default choice” because Lean seems to have the largest active community, especially when it comes to classically trained mathematicians who want to prove standard math results and don’t necessarily care about experimenting with different foundations or logical frameworks. Because of this, I will focus on Lean 4, but know that a lot transfers to other proof assistants based on Dependent Type Theory such as Agda or Rocq.

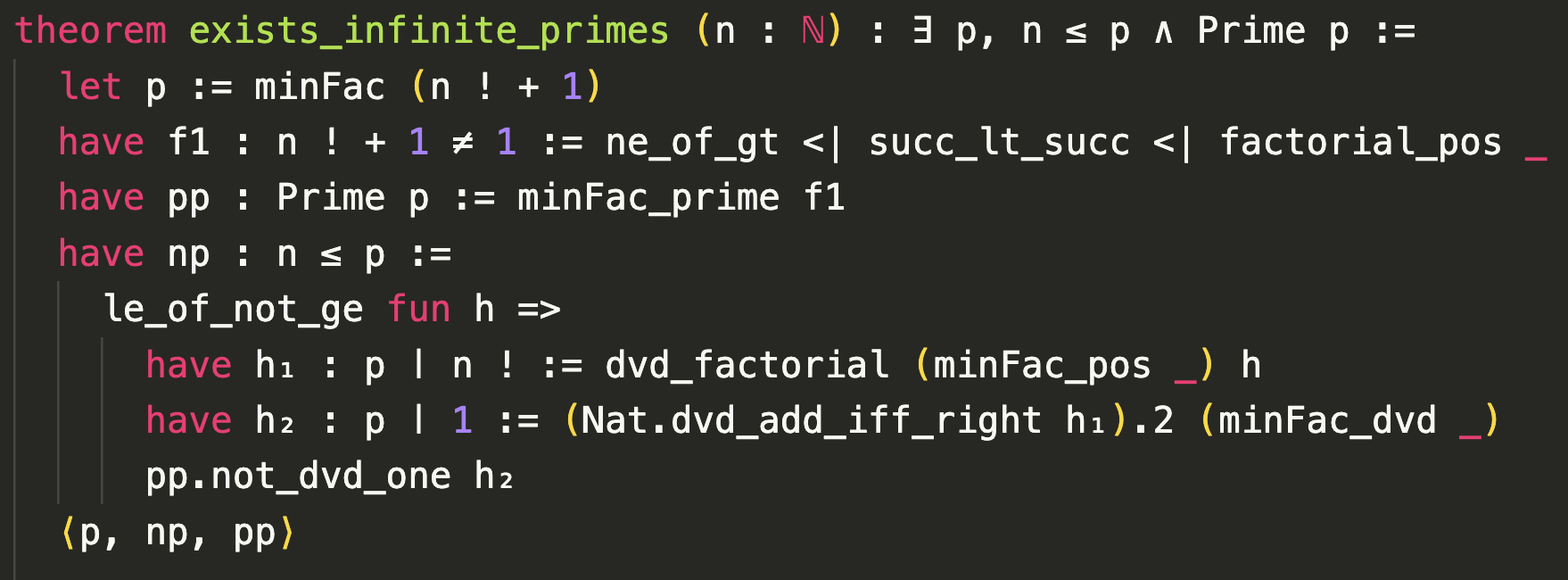

Lean 4 proof of Euclid’s theorem on the infinitude of primes, in Mathlib/Data/Nat/Prime/Infinite.lean.

In terms of tutorials, there are two excellent free online books: Mathematics in Lean and Theorem Proving in Lean 4. If you are wondering which one to start with, here’s an excerpt from the former one (clarification mine):

Theorem Proving in Lean is for people who prefer to read a user manual cover to cover before using a new dishwasher. If you are the kind of person who prefers to hit the start button and figure out how to activate the potscrubber feature later, it makes more sense to start here [Mathematics in Lean] and refer back to Theorem Proving in Lean as necessary.

There’s also The Natural Number Game, which is a game-like introduction to mathematical proofs in Lean. If you want to follow a course, I strongly recommend Stanford’s CS 99: Functional Programming and Theorem Proving in Lean 4, but keep in mind that formalization of mathematics is not the only focus of the course.

Lean 4 has an impressive mathematical library, the mathlib library, which includes a lot of fundamental and advanced mathematics. There exist search tools such as Lean finder and LeanSearch that allow for natural language, semantic search in the library, which can be extremely useful.

Other great resources include the Lean reference manual, a list of resources in the official Lean website, the Lean Community website, and the Official Lean blog.

Finally, in terms of getting help, there’s the highly active Lean Zulip channel, and keep in mind that Lean is a programming language, so tools like coding agents and general purpose LLMs can help with debugging, can provide examples, and can aid in digesting concepts.