Artificial Mathematical Intelligence in 2025

Artificial Intelligence can be applied to many math-related tasks, including formal and informal theorem proving, formalization and informalization, and math discovery. In order to make long term progress, it is necessary to have a good understanding of each task, of their relationships, and of what is currently within reach.

I believe that math formalization will play a central role in Artificial Mathematical Intelligence. If you are not familiar with formalization, you can check my previous post on Why math should be formalized.

Acknowledgements. I took the term “Artificial Mathematical Intelligence” from a talk by Emily Riehl, which I recommend. I thank Leni Aniva and Justin Asher for conversations about these topics.

Contents

What is Artificial Mathematical Intelligence

Mathematicians perform many tasks, such as coming up with new statements and theories, proving results, typing results and proofs in LaTex, and, more and more, formalizing statements and results in a proof assistant. Any of these tasks can potentially be automated, and this automation is what I refer to as Artificial Mathematical Intelligence (AMI). In this post, I will focus on the following three tasks, but I say a bit about other tasks below.

-

Informal Theorem Proving: Given a mathematical statement (either formal or informal), provide an informal proof of it.

-

Formal Theorem Proving: Given a mathematical statement formalized in a proof assistant, provide a formal proof which is accepted by the proof assistant.

-

Formalization: Given a mathematical theory described in informal language, formalize this theory in a proof assistant in a way that is accepted by the proof assistant. By mathematical theory, I mean any collection of definitions, result statements (ie the statement of a theorem, proposition, or lemma), and proofs.

When performed automatically using, for example, a combination of Machine Learning and Formal Methods, I’ll refer to these tasks as Automatic Informal Theorem Proving, Automatic Formal Theorem Proving, and Autoformalization, respectively. There are important connections between these three tasks that are leveraged in practice, and I’ll discuss this below.

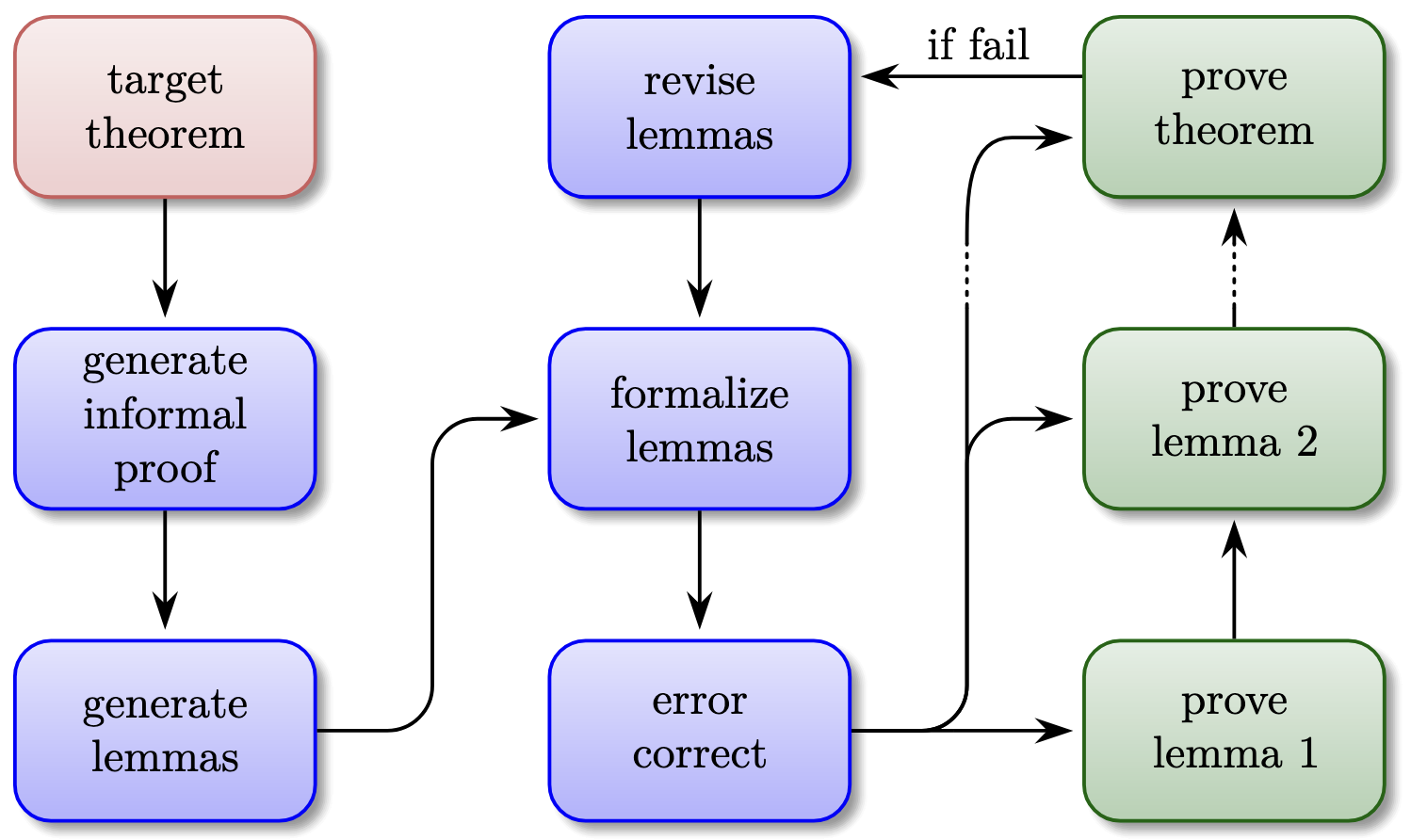

The three Artificial Mathematical Intelligence tasks considered in this post, and some of the main relationships between them.

Other tasks. There are many other important tasks. These include specific tasks such as solving exercises (similar to theorem proving, but might just involve a computation and not a proof), performing calculations or simplifications (such as simplifying a complicated integral), finding counterexamples or interesting examples, as well as more complex tasks such as mathematical discovery, that is, coming up with new theories, conjectures, constructions, or proof strategies, formal or informal. For more on this, see for example [Bengio, Malkin. Bull. AMS], [Riehl. Talk], [Frieder et al.], and [Novikov et al.]. Another important task is informalization: given a formalized mathematical theory, provide an informal version of it. This task will become especially relevant with formalization at scale, since it will aid in understanding formalized proofs that were not produced by humans.

Before getting into more details, we need to discuss a fundamental problem that needs to be addressed when developing AMI.

The semantic gap

A semantic gap is a disconnect between two semantic frameworks. For instance, a semantic gap manifests whenever any two agents (human or AI) communicate in such a way that there exists the possibility that one agent is misrepresenting the intention of the other1. A down-to-earth example of a semantic gap is when your colleague in a different timezone misinterprets the time for your meeting.

The semantic gap affects two of the main mathematical tasks that I described earlier: Autoformalization and Automated Informal Theorem Proving. How the semantic gap affects Autoformalization is straightforward: the formalized output may or may not represent the intention of the agent (human or AI) that produced the informal input to the Autoformalizer. For example the mathematical term “prime” in the figure below might mean “prime integer” or “prime element” of some other ring:

The semantic gap affects Automated Informal Theorem Proving in two ways: one, the Automated Informal Theorem Prover could misinterpret the input; and two, the output of the prover could be misinterpreted by another agent. This makes evaluating an Automated Informal Theorem Prover especially delicate.

The semantic gap does not affect Automatic Formal Theorem Proving; and in a sense, this is exactly the point of formalization! It is important to recognize this, since it can be leveraged in practice: In Machine Learning terms, an agent can be trained to produce formal proofs using verifiable rewards, since each proof step can be objectively checked by the proof assistant.

Unfortunately, we can’t only work with formal math (at least for now), so in many applications we need to mitigate the semantic gap. I’ll discuss this more when describing each of the main tasks below.

Theorem Proving

Let us start with Formal and Informal Theorem Proving, and, more generally, by being more specific about what the goal is. There are at least two tasks that one can refer to theorem proving.

-

In Novel Theorem Proving the goal is to provide a proof for a conjecture or for a new result that hasn’t been considered before. Novel Theorem Proving can be seen as the holy grail of AMI, since it could involve providing proofs for long-standing mathematical conjectures.

-

A simpler task is Known Theorem Proving, where the goal is to provide a proof for a result for which a proof strategy is known and believed to work. Known Theorem Proving can be useful, for example, for understanding complicated or imprecise proofs, for filling in details, and for making sure that there are no gaps in an argument.

For a 2024 survey on ML methods for Theorem Proving, you can check [Li et al.].

Automated Formal Theorem Proving

Classical approaches and Formal Methods. Classical approaches to AFTP rely on Formal Methods, a set of techniques and tools used to mathematically specify, design, and verify complex systems (typically software). For example, modern proof assistants allow for specification via formal mathematical definitions, design via programs, and automated machine-checked verification of formal proofs. Before the current wave of AI integration, automation was based on search achieving dramatic efficiency gains through key algorithmic breakthroughs:

- The Resolution Principle and the Unification algorithm[Robinson. JACM], which reduce complex logical inference to a single, efficient rule of refutation.

- Conflict-Driven Clause Learning[Moskewicz et al. DAC], a SAT solving method that prunes vast regions of the search space.

- The Superposition Calculus[Bachmair, Ganzinger. J. Log. Comput.], a powerful framework for equational reasoning.

These techniques are integrated into specialized tools such as Satisfiability Modulo Theory solvers (SMT solvers), which represent the state-of-the-art of search-based formal deduction. On top of these, hammers act as a translator between these automated tools and proof assistants. Hammers are examples of tactics, which are proof assistant functions that a user can call to automate part of the formalization process. For more about the subject, you can check, for instance, the textbook [Kroening, Strichman. TTCS] on formal reasoning, and the papers [Limperg, From. CPP] and [Norman, Avigad. ITP] on a SOTA search-based tactics for AFTP in Type Theory.

Current approaches. Recently, significant progress has been made in AFTP using Machine Learning. While specific implementations are often complicated in the details, they usually rely on some of the following techniques:

-

Agents based on Large Language Models (LLMs). This approach builds an AI agent consisting of an LLM that interacts with a proof assistant essentially like a human does, by directly producing code and using the proof assistant as a tool (eg, using [Dressler. Git]). By treating formalization as a coding task, one can reuse infrastructure developed for AI coding agents. There are at this point many implementations that use this approach. For example [Goedel-Prover-V2] fine-tunes a Qwen3 model, while [Delta Prover] is based on an agentic framework around an off-the-shelf LLM with no further training.

-

LLMs for informal reasoning. Here, the informal reasoning capabilities of LLMs are leveraged in several ways, including first producing an informal proof and then attempting to formalize it[Jiang et al. ICLR], generating possible useful lemmas and intermediate steps, guiding a formal theorem prover[Seed-Prover][Harmonic Team][Varambally et al.], or interleaving formal and informal reasoning[Kimina-Prover Preview].

Figure from [Harmonic Team]. A high-level illustration of the approach to AFTP implemented in the Aristotle agent. Notice in particular that it leverages AITP to generate possibly useful lemmas.

-

Reinforcement Learning (RL). This approach interprets theorem proving as an iterated decision problem, and uses techniques from RL to train or fine-tune an agent that, at each step, proposes a set of candidate tactics to try next, and tries to predict the expected return from applying these tactics. For more details on this point of view, you can check AlphaProof’s paper [Hubert et al. Nature] and [Kimina-Prover Preview].

-

Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). This is a stochastic search algorithm that incrementally builds and explores a search tree using randomized simulations to estimate promising paths, and it is key in the success of ML models for games such as chess and Go. The use of MCTS for theorem proving was proposed in [Färber et al. CADE], and SOTA approaches use MCTS with various modifications; see, eg, [DeepSeek-Prover-V1.5. ICLR] and [Harmonic Team]. It is important to recognize that search in the context of theorem proving has several subtleties, such as metavariable coupling; you can read more about this in [Aniva et al. TACAS].

-

Test Time Training. This is also described in [Hubert et al. Nature], and the idea is roughly the following: given a target statement, produce a set of variations and fine-tune the model using RL on those variations. The fine-tuned model is then used to attempt to prove the original statement.

-

Domain-specific solvers. The typical examples are geometry solvers such as AlphaGeometry[Trinh et al. Nature], which is a specialized theorem prover for Euclidean plane geometry.

In all of the approaches above, Formal Methods are incorporated quite indirectly, by allowing the model to invoke proof assistant tactics that implement the methods outlined earlier, such as Lean’s SMT solver tactic smt.

Training data: math as a game, zero human knowledge, self-play. A big difficulty when training AFTP models is gathering enough good quality data, and this might be the main current bottleneck. Formal math libraries such as Lean’s mathlib, while extremely impressive and useful, are orders of magnitude smaller than what a large scale model needs (at least with the current models and training techniques). Another issue is data contamination: approaches relying on LLMs are often tested on data the LLM was (potentially) trained on, which can make evaluation difficult.

In practice, datasets are produced in large part using Autoformalization (hence the arrow from Autoformalization to AFTP in the figure at the beginning of the post). This comes with several issues: for one, Autoformalization is imperfect, but also it is not known if algorithms trained exclusively on human data will generalize. It is also unclear if human knowledge is useful for Formal Theorem Proving, or if there exist learning algorithms that can find better, more efficient proofs without human knowledge. This would be similar to how algorithms such as AlphaZero are able to learn how to play board games at a superhuman level without any human input.

Still in the context of board games, it is also interesting to recall that lack of data was overcome using self-play[Samuel. IBM J. Res. Dev.]: such games are symmetric, so a single model can be trained by playing against itself. Unfortunately, theorem proving has no such simple symmetry: coming up with a mathematical statement seems, a priori, like a very different task from proving a statement. Nevertheless, it is plausible that a useful analogue of self-play for theorem proving exists, and this could have a big impact. Self-play in the context of AMI is explored in [Dong, Ma]. It is also possible that true superhuman AFTP agents can only be trained at the same time as superhuman math discovery agents.

Do we need language models and informal reasoning? The usage of LLMs for informal reasoning works well in practice for simple proofs (hence the arrow from AITP to AFTP in the figure) but it is not clear that such approaches will scale to truly difficult proofs. Going back to the comparison between math and games, note that it is actually not straightforward to fine-tune a SOTA LLM to play chess or Go to the same level as, say, AlphaZero[Schultz et al. ICML][Ma et al. NeurIPS]. One could read this as saying that those games are fundamentally not about language, so an LLM may not be the best tool for the job. The same could be true for math, which I would guess is also not fundamentally about language. Personally, I think that at a certain point informal reasoning will become a bottleneck when it comes to AFTP, but it is not clear at what point this will happen, and it is likely that a lot of progress can be made with LLMs.

What can current agents prove? So far, and to the best of my knowledge, AFTP agents have performed well in limited contexts, such as olympiad-type problems. Their performance in this context is impressive: for example, Aristotle[Harmonic Team] achieved a gold-medal-equivalent performance on the 2025 International Mathematical Olympiad by providing correct formal solutions to five out of six problems. For an up-to-date comparison of different models, you can check [PutnamBench Leaderboard], which includes the performance of SOTA models on an olympiad-type dataset. As an example of Novel Theorem Proving, Aristotle provided a proof for an “easy version” of a conjecture by Erdős, although this is still regarded as “olympiad-style” math. To the best of my knowledge, we have not yet reached the point when an AI agent proves or disproves a long-standing mathematical conjecture.

Automated Informal Theorem Proving

State-of-the-art Automated Informal Theorem Provers are based on LLMs. Most commonly, the starting point is a general purpose LLM that has been trained on large portions of the internet. The LLM is then fine-tuned on informal mathematical corpora such as text books, mathematical articles, and specialized datasets. The main technique that enables these models to solve mathematical problems, and to reason more generally, is chain-of-thought (CoT)[Wei et al. NeurIPS], where the model is trained to generate intermediate steps before a final answer. CoT can be used for self-reflection, self-verification, and correction.

Examples of agents that rely on CoT to solve mathematical problems and provide mathematical proofs include [DeepSeekMath-V2], and many of the general purpose models such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. The FrontierMath benchmark project keeps track of the performance of many of these models on a series of math problems. Some care has to be taken when interpreting these results: first, only final answers to problems are evaluated, so this may not reflect the performance of the models when producing proofs; second, to avoid data contamination, the problems are not public, so we don’t exactly know what is being evaluated. The potential issues of evaluating models solely based on a final answer are considered in [Petrov et al. ICML AI4MATH workshop].

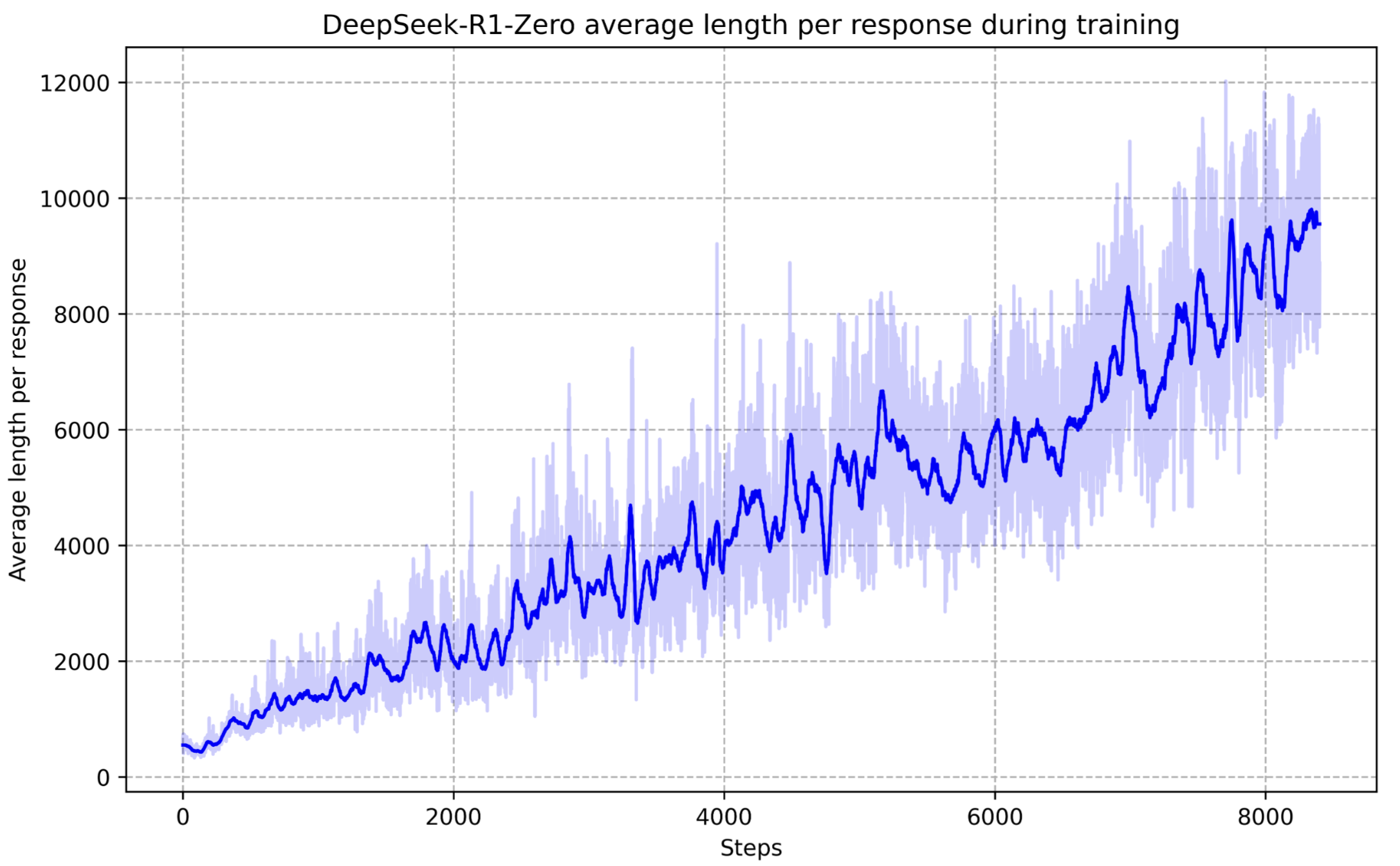

Figure from [DeepSeek-AI], where caption reads as follows The average response length of DeepSeek-R1-Zero on the training set during the RL process. DeepSeek-R1-Zero naturally learns to solve reasoning tasks with more thinking time. The paper demonstrates that emergent CoT-like behavior can arise in RL-trained reasoning agents, where more complex tasks require longer reasoning traces.

AITP can be useful for guiding AFTP, informalization, and explanation of known proofs, and it may or may not be the case that AITP is in necessary for AFTP. Regardless of this, I believe that AITP by itself cannot scale to Novel Theorem Proving, due to the semantic gap and the human-AI asymmetry of informal math, that is, the fact that both a human and an AI can produce informal math, but only a human expert can verify it (which I observe in Why math should be formalized). This asymmetry puts a hard limit on how much AITP-produced math can reliably be verified.

Autoformalization

There are lots of proposed approaches to Autoformalization (for early references, see, eg, [Wang et al. CPP][Wu et al. NeurIPS][Szegedy. CICM]). I will not say too much about this since, in my experience, this problem is significantly easier to address than AFTP and AITP.

I find that current SOTA LLMs are actually pretty decent at Autoformalization, if including the right references in the context, and if incorporated into an agent that can use the proof assistant’s output as feedback to iteratively fix the formalization until it compiles. Two other techniques that can make a significant difference are using informal math-guided AFTPs for formalizing proofs, like for example Aristotle[Harmonic Team] (hence the arrow from AFTP to Autoformalization in the figure), and using blueprints[Lean blueprints], that is, first organizing the mathematical theory into definitions and statements with dependencies, and then formalizing these one by one.

The main thing one needs to watch out for is the semantic gap, which can be addressed to a reasonable extent by using an LLM-as-a-judge[Zheng et al. NeurIPS], in this case by adding one or more agents to the pipeline whose job is to identify and point out to the formalizer potential semantic gaps. In order to use these ideas to reach a satisfactory pipeline, one or more mathematicians need to be consulted, since, as I mentioned previously, only a mathematician (in fact, an expert in the field) can function as a reliable safeguard against the semantic gap.

I believe that, in the short term, more and more math will be formalized using technologies that we already have. Large scale formalized libraries will most likely enable the training of AI agents that can really make progress in Formal Novel Theorem Proving.

-

In the context of AMI with black-box models, I have also seen this concept referred to as the intention problem[Aniva. Blogpost]. ↩